Happy New Year from the mountains of Japan where I’m hitting the ski slopes, eating some delicious meals and soaking up some fantastic Japanese hospitality. Last night we were served the traditional midnight meal of Soba Noodles by our hosts at the Sidehill Lodge in Hakuba, Nagano Prefecture.

I’m a fan of utilizing passive ultrasonic irrigation (PUI) to improve the effectiveness of our irrgants, and believe that it produces root canals with fewer debris and bacteria than needle irrigation alone. Recently there has been some talk about the use of lasers to activate our irrigants in a similar manner and there is at least some evidence that this may improve the cleanliness. Here is a promotional video to give you a brief overview:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0dLJWm6LGk&feature=related

Now, we are still waiting on evidence to prove that any of these methods provide a better outcome in terms of healing or prevention of apical periodontitis, but in the meantime, we should be aiming to produce the cleanest canals we can.

My colleague Mateus Miranda has volounteered to look into the use of lasers to activate irrigants and has produced a nice overview of the available evidence. The key paper so far is probably the one by Ove Peters in the JOE in 2011 showing an improved ability of the technology to reduce, but not remove bacteria from intra-orally infected teeth.

Enter Mateus……….

There has been recently introduced onto the dental market a said “revolutionary” mechanism for cleaning and debriding of root canal systems. The PIPS uses Erbium: Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (Er:YAG) laser energy at sub-ablative power levels which produces wavelengths of 2940nm. PIPS was developed by Dr. Enrico DiVito with assistance from Dr. Mark Colonna.

This non-visible-to-human-eye laser energy is strongly absorbed by water and when activated with specific peak power derived from short pulse duration results in a photomechanical phenomenon or photo-ablation on dentin, allegedly removing smear layer and exposing dentinal tubules.

The Er: YAG laser was tested for the first time in 1988 for preparing dental hard tissues. It was successfully used to prepare holes in enamel and dentine with low ‘fluences’ (energy (mJ)/unit area (cm2)). In 1989, it was demonstrated that the Er: YAG laser produced cavities in enamel and dentine without major adverse side effects (A. HUSEIN 2006).

In 1998 a study performed by TAKEDA FH and colleagues concluded “The root canal walls irradiated by Er:YAG laser were free of debris, with an evaporated smear layer and open dentinal tubules. These results suggested that Er:YAG laser irradiation had an efficient cleaning effect on the prepared root canal walls. FLAVIO SOARES et al (2008) found laser cleanliness in root walls of primary teeth was similar with rotary instruments and superior to manual instrumentation and it required less time for completion. KYOKO INAMOTO et al in 2009 found no smear layer presence following instrumentation of root canal walls using the same laser therapy.

Irrigation wise, ROELAND JG De MOOR et al (2010) showed the efficacy of Laser Activated irrigation (LAI) using Er:YAG for 20 seconds compared to Passive Ultrassonic Irrigation (PUI) for 60 seconds for dentinal debris removal. DIVITO et al (2010) concluded the Er:YAG laser used in this study showed significantly better smear layer removal than traditional syringe irrigation.

Considering thermal effect, studies were performed and were conclusive on the safety of the Er: YAG lasers usage unless proper water cooling and specific power output setting was used (V ARMENGOL et al. 2000, REMI YAMAZAKI et al. 2001, KIMURA et al. 2002, B N CAVALCANTI et al.2003).

Most importantly some studies tested the efficacy of the bactericidal effect of the Er: YAG laser, particularly on Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis and were happy to concluded positively (MORITZ A. 1999, Loma Linda University School of Dentistry.2010). However, a study conducted by OVE A PETERS et al (2011) showed activated disinfection did not completely remove oral bacteria from the apical root canal third and infected dentinal tubules, requiring some further investigation.

But how does PIPS® actually work?

After gaining access to the canal, an instrumentation of the canal is done to ISO #20 only. No further enlargement is necessary thus preserving tooth strength.

This is followed by PIPS® activation delivered from a cone-shaped fiber tip attached to a handpiece within an irrigating solution, either EDTA or NaOCl. The tip is inserted into the coronal third of the canal thus there is no risk of tip breakage from curved canals or undesirable apical extrusion of chemical irrigants possible with other laser endodontic methods (ROY GEORGE et al, 2008). The canal system is finally flushed clean with water and is ready to be obturated.

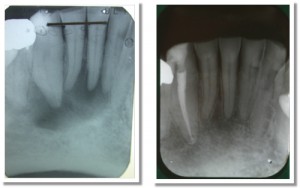

It is worthy it to check on the images provided by Dr Enrico DiVito and its team related to this new mechanism of root canal debridement. Please follow the link.

To sum up, this new technology seems to be very effective and efficient regarding root canal therapy. The ability to prepare/ instrument canals in a short period of time associated with great reduction of bacterial count (when compared to conventional root canal instrumentation) is absolutely promising.

References:

A. Husein. 2006. Applications of Lasers in Dentistry: A Review.

Takeda FH, Harashima T, Eto JN, Kimura Y, Matsumoto K. 1998. Effect of Er: YAG laser treatment on the root canal walls of human teeth: an SEM study.

Flavio Soares, Claudio H. Varella, Roberta Pileggi, Abi Adewumi, Marcio Guelmann. 2008. Impact of Er,Cr:YSGG Laser Therapy on the Cleanliness of the Root Canal Walls of Primary Teeth.

Kyoko Inamoto, Naoki Horiba, Shinpei Senda, Munetaka Naitoh, Eiichiro Ariji, Akira Senda, Hiroshi Nakamura. 2009. Possibility of root canal preparation by Er: YAG laser.

Roeland J.G. De Moor, Maarten Meire, Kawe Goharkhay, Andreas Moritz, Jacques Vanobbergen. 2010. Efficacy of Ultrasonic versus Laser-activated Irrigation to Remove Artificially Placed Dentin Debris Plugs.

E. DiVito, O. A. Peters, G. Olivi. 2010. Effectiveness of the Erbium:YAG laser and new design radial and stripped tips in removing the smear layer after root canal instrumentation.

V. Armengol, A. Jean, D. Marion. 2000. Temperature Rise During Er: YAG and Nd:YAP Laser Ablation of Dentin.

Reimi Yamazaki, Claudia Goya, Da-Guang Yu, Yuichi Kimura, Koukichi Matsumoto. 2001. Effects of Erbium, Chromium:YSGG Laser Irradiation on Root Canal Walls: A Scanning Electron Microscopic and Thermographic Study.

Yuichi Kimura, Kazuo Yonaga, Keiko Yokoyama, Jun-ichiro Kinoshita, Yoshiko Ogata, Koukichi Matsumoto. 2002. Root Surface Temperature Increase during Er: YAG Laser Irradiation of Root Canals.

Bruno Neves Cavalcanti, José Luiz Lage-Marques, Sigmar Mello Rode. 2003. Pulpal temperature increases with Er:YAG laser and high-speed handpieces.

Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, Jakolitsch S, Kluger W, Wernisch J, Sperr W. 1999. The bactericidal effect of Nd:YAG, Ho:YAG, and Er:YAG laser irradiation in the root canal: an in vitro comparison.

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry. 2010. Final Report: Efficacy of Er: YAG Laser on Root Canals Infected with Enterococcus faecalis.

Ove A. Peters, Sean Bardsley, Jennifer Fong, Goldie Pandher, Enrico DiVito. 2011. Disinfection of Root Canals with Photon-initiated Photoacoustic Streaming.

Roy George, Laurence J. Walsh. 2008. Apical Extrusion of Root Canal Irrigants When Using Er: YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG Lasers with Optical Fibers: An In Vitro Dye Study.

Hyperlink: http://www.fotona.com/media/aurora/dokumenti/2010/11/pips_brochure_fotona_web.pdf