In this post, we discuss a simple and practical method of classifying pulpal pathology that can be used in practice on a daily basis. For the new and updated Endospot Podcast, go to the Podcast Page.

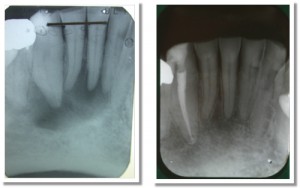

How do you classify the pulp in this tooth?

Listen to the episode here (12 minutes):The Endospot Episode 2 | Simple Guide to Pulpal and Periapical Diagnosis Part 1

References Referred to in This Episode:

BARBAKOW F, CLEATON-JONES P, FRIEDMAN D. Endodontic treatment of teeth with periapical radiolucent areas in a general practice. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1981. 51, 552–559.

BENDER IB. 2000 Pulpal Pain Diagnosis. A Review. J Endod 2000. 26, 175-179

BENDER IB. 2000. Reversible and irreversible painful pulpitides: diagnosis and treatment. Aust Endod J 2000. 26, 10–14.

MILES TS. Dental pain: self-observations by a neurophysiologist. j Endod 1993. 19, 613-5.

SELTZER S, BENDER IB, ZIONTZ M. The dynamics of pulp inflammation: correlations between diagnostic data and actual histologic findings in the pulp. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1963. 16, 846-71 and 1963. 16, 969-77.

SIGURDSSON A. 2003. Pulpal Diagnosis. Endodontic Topics. 5, 12-25.

Transcript:

Welcome to the Endospot Episode 2.

My Name’s Pat Caldwell and today we’re coming to you from Shanghai, China. On our website we have the complete list of references discussed in this episode, so go to www.endospot.com and remember you can sign up online to receive the Endospot directly to your inbox.

In this episode, we’ll be discussing the classification of pulpal pathology. This will be the first in a series of three episodes looking at the issue of diagnosing pulpal and periapical pathology and in this episode we’ll go through a useful classification system which will help you deliver appropriate treatment to your patients. I’ve broken it up into three episodes because diagnosing and therefore treating appropriately is just so important. I think that often not enough time and thought goes into the initial diagnosis and that is when errors are made and our patients suffer. As endodontists we often see cases where an incorrect diagnosis has been made and treatment either withheld or provided when it wasn’t required and as professionals we owe our patient more than that.

When we look at the pulp and periapical classification systems, there are many out there, but in my opinion the simplest and most useful is the one proposed by Asgir Sigurdsson (Sigurdsson 2003). He published an excellent journal review article on this particular topic in everyone’s favourite journal, Endodontic Topics and that’s the classification system I’ll be discussing today. This classification is very much designed to give a clear indication of the treatment requirement according to the diagnosis, and when it comes down to it, that’s what we’re really looking to achieve out of our diagnosis.

Now when I’m faced with a new patient, whether they are presenting in pain or not, I will still conduct a complete history and examination and make both a pulpal and periapical diagnosis. I split the diagnosis into pulpal and periapical because it helps me have clear in my mind exactly what I’m dealing with, how we should proceed and what follow up’s required. It will also give us clues as to what problems we might run into, such as if the tooth will be difficult to anaesthetise, or if there’s likely to be a high level of post-operative pain. To be fair it will most often be the pulpal diagnosis that is driving your treatment decisions and that’s another reason to spend an episode on going through the various diagnoses.

Now if you think about it, the only way we can definitively diagnose the state of a pulp is to extract the tooth and slice it up and look at it through a microscope. So, our clinical diagnosis is always going to include an element of a guess and I can assure you that it will not always be straightforward. But I dIgress, we’ll get onto how to diagnose in a future episode so now let’s get back to the topic at hand. The classification system we are going to be using includes 4 different diagnoses for the dental pulp, and one of them is the healthy pulp. That’s the easiest one so we will start with that one.

A diagnosis of healthy pulp assumes that the pulp is vital and is not inflamed in any way. This tooth will respond normally to pulp testing, that is hot, cold and electric. It will be asymptomatic and shouldn’t be tender to percussion or palpation unless there is an occlusion issue causing this. We use this classification sometimes when we need to do RCT on a tooth for prosthodontic reasons. So an example might be where there is not a lot of coronal tooth structure remaining in a vital tooth and the restorative dentist feels that an intracoronal restoration is required in order to provide retention for a core.

We’ll now move on to the more complex diagnoses, the ones indicating some sort of inflammatory response. The first of these is Reversible pulpitis. If we looked at this pulp under a microscope, we’d see a vital pulp with areas of localised inflammation. Most commonly this will be associated with a response to caries or possibly microbial leakage of a restoration. It could also be due to exposed dentine or bacterial ingress along a crack. All these things will lead to inflammation in the pulp. Now by definition, this inflamed pulp should heal when we remove the cause of the inflammation, so it’s important not to misdiagnose this pulp with an irreversible pulpitis and initiate RCT when it’s not needed.

A pulp with reversible pulpitis can present with quite a broad range of symptoms. Typically, the patient will describe pain with hot or cold, or with biting in the case of a crack. The pain might be mild, but can sometimes be severe, but probably the key to this diagnosis is that removal of the stimulus will lead to rapid relief of the pain. For example, drink something hot, tooth hurts, swallow the drink, tooth is fine. In general, there should also be no report of spontaneous pain, and no tenderness to percussion or palpation. The tooth is likely to respond to a pulp test, but the inflammation in the pulp might mean that an exaggerated response is gained. This in itself isn’t an indication of irreversible pulpitis, if the other indicators are that of reversible inflammation.

When you diagnoses reversible pulpitis and remove the stimulus by removing caries, or covering exposed dentine, it’s important that you review the patient and re-do all the examination procedures. Because if you think about, if you’ve diagnosed reversible pulpitis, say in case where there is a carious lesion and you treat it by removing the caries and placing a restoration, but the symptoms remain then by definition the pulp wasn’t reversibly inflamed.

Choosing between a diagnosis of reversible pulpitis, and it’s for more unpleasant alternative irreversible pulpitis is a critical decision, because the treatment options are very different. Where a pulp is irreversibly inflamed, this means that the inflammation is so severe that the pulp will not be able to heal. It will eventually necrose and become infected, leading to apical periodontitis. The treatment for these teeth is to undertake root canal therapy in order to remove the diseased pulp tissue and prevent infection.

As with reversible pulpitis we see a wide range of presentations. Commonly there is an exaggerated response to hot and cold, but the key here is that this response lingers for some time. It’s hard to say exactly how long it has to linger to be considered irreversible, so here I’ll have to take some licence and say that a pain that lingers for a number of minutes after stimulus is not a healthy pulp. There is a good biological explanation for this lingering pain but I’ll go through that with you in the diagnosis episode. Sigurdsson tells us to be careful when interpreting this symptom as if you put an intense stimulus even on a healthy pulp the resulting pain will linger somewhat.

Another indicator that we’re dealing with an irreversibly inflamed pulp is where the pain has been severe, and the longer it has been present, the more likely it is to be irreversible in nature (Bender 2000). When pulp testing this tooth, there will often be an exaggerated response and the dull lingering pain experienced before will be induced by the procedure. Tenderness to percussion is often also present. The level of inflammation in these teeth will often lead to neurogenic pain and nerve sprouting which results in inflammation in the periapical tissues. This can occur well before the pulp starts to die and therefore even in a vital, inflamed pulp, tenderness to percussion is often present.

Probably the biggest indicator of an irreversibly inflamed pulp is spontaneous pain. So the patient will report moderate to severe pain that suddenly occurs, and often remains as a dull lingering pain for minutes or hours. They might even report being woken by the pain. I often find that patients with irreversible pulpitis have resorted to over the counter painkillers such as ibuprofen and report that these drugs will help relieve the pain until they wear off of course.

There is an excellent article published by Timothy Miles, who is a neurophysiologist who had previously trained as a dentist (Miles 1993). In the article he explains in detail his not only the physiological response he personally experienced due to a dying pulp, but also the emotional response. It has a grand total of 6 references which it probably could have done without and yet was published in the Journal of Endodontics. It’s probably essential reading for any dentist who has never experienced toothache, and I’ll put the reference in the show notes. If you ever sit the examinations for the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, then I believe he still lectures on the primary orientation course, and you can have the pleasure of hearing the story in person.

Our final diagnosis is pulpal necrosis. This covers both partial and complete necrosis of the pulp. Consider the progression from reversible pulpitis to irreversible pulpitis and on to pulpal necrosis. At some point the inflammation builds to a level where the vital tissue dies. This necrosis over time then spreads throughout the whole pulp space. There isn’t a lot of information on exactly how quickly the process occurs and I imagine that there is a great variation in the length of that process, but when it comes down to it, some form of Root canal therapy is required.

Most of the time when a pulp is necrotic, it will also be infected. There are a few situations where a pulp can necrose and remain uninfected, mostly after physical trauma to a tooth, but on the whole, a dead pulp lacks a blood supply and therefore lacks the ability to protect itself against microorganisms. These bugs will get into the pulp space through cracks or infected dentine, or possible exposed dentinal tubules and rapidly take over the necrotic space.

When dealing with a patient presenting in pain, there is a strong correlation between the following factors and pulpal necrosis. First is a history of moderate to severe pain. Second is tenderness to percussion, third is a history of spontaneous pain and fourth is a negative pulp test. Seltzer and Bender conducted some of the most useful research we have on this topic way back in 1963 (Seltzer et al. 1963). Basically, they examined patients who presented with pain and then the tooth was extracted and examined histologically. There is a nice summary of their findings in a paper published by IB Bender in 2000 in the JOE which you should read if you are a postgraduate student (Bender 2000).

It’s important to note here though that very often the progression from vital to necrotic pulp is painless, or the level of pain is minimal and no help is sought for the problem. Often patients are completely unaware that they have a chronic infection in their jaw. Two studies reported this happening in 26-60% of cases. (BARBAKOW ET AL. 1981, BENDER 200) In my experience these teeth may be completely asymptomatic. They can be slightly tender to percussion but often don’t even present with this. Usually, they are identified due to a lucency on a PA or OPG Xray. The key for these though is that they will not respond to a pulp test and can be entered without local anaesthetic.

OK, I think that’s enough for this episode. Next episode we’ll be discussing the various periapical diagnoses that we can make. In the meantime, I recommend you have a look at the references, and next time and every time you work on a tooth, have a think about what diagnosis you have for the pulp. If you’re placing large restoration or crown think about whether you’re completely confident of your diagnosis before doing the work.

Also, if you’ve got a comment, or you disagree with something that was said here, please keep it nice, but I’d love you to go to the blog and leave a comment.