There are a huge number of factors that can affect the outcome of endodontic therapy. Attempting to isolate these individual factors and determine the relative importance of each is something that has proven difficult or impossible in endodontic scientific literature.

Ultimately, our primary aim is to allow our patients to keep their teeth for the rest of their lives. The evidence we have available points to the majority of endodontically treated teeth surviving for long periods of time. (1) Those that are extracted most commonly fail due to non-endodontic reasons. The most common cause of extraction of root filled teeth is crown fracture and periodontal disease.(2)

In terms of crown (and root) fracture, I believe that the conservation of dentine in the crown and in the region a couple of mm just above and below the cervical area is essential to providing ongoing resistance to fracture. In order to have as strong a tooth as possible, we need maximum thickness of tooth structure in this area.

In terms of this, I see that using strategies to limit the amount of tooth structure loss during endodontic access as one of the most important measures that can be taken to ensure the greatest longevity for root filled teeth. Of course, we still need to achieve the aims of endodontic treatment, but this shouldn’t come at the cost of doing irreversible damage to the crown of the tooth that may compromise the tooth’s long term survival.

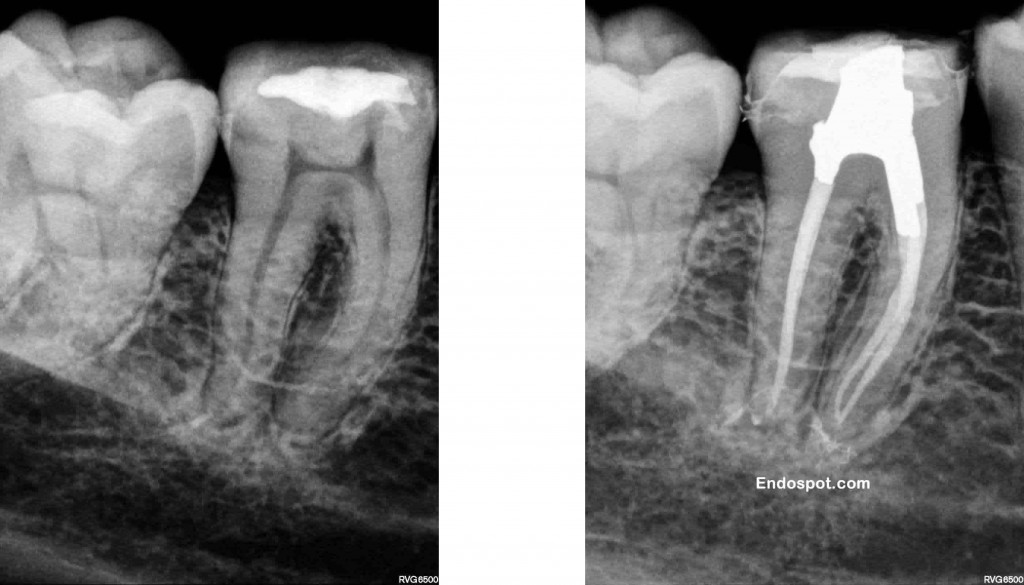

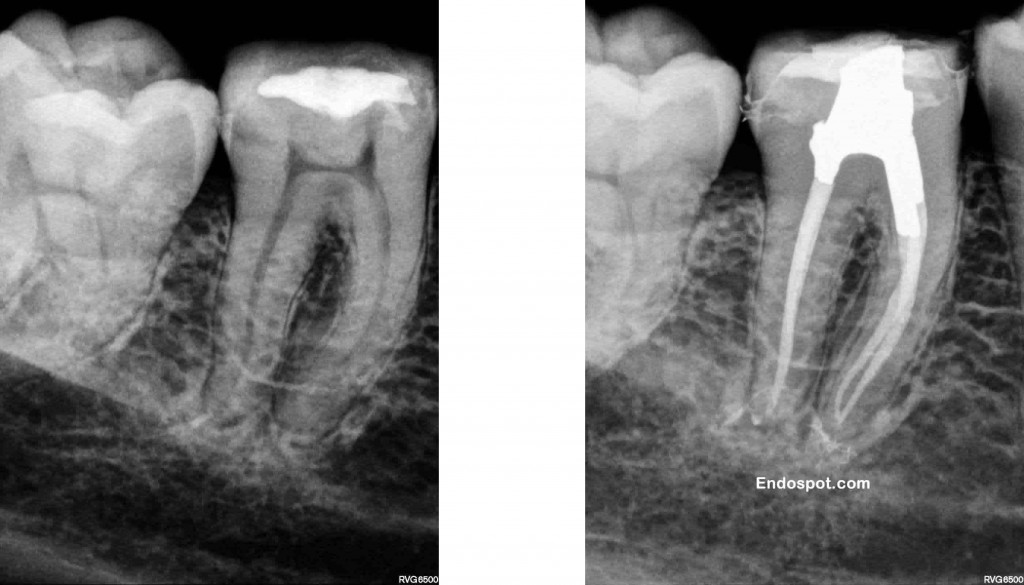

Endodontic access has been performed which gives good access to the canal orifices. But imagine the thickness of dentine that will remain mesially and distally if a crown was prepared for this tooth. The endodontics can be perfectly performed, but the tooth is compromised due to the excessive loss of tooth structure during access.

This is why we aim to keep access limited and you will sometimes see what appears to be incomplete opening of the pulp chamber. This is by design and allows important tooth structure to be maintained that contributes to the strength and durability of the tooth. Strategies for conserving tooth structure during endodontic access include removing restorations and caries and utilising this space for endodontic access. A good discussion of these strategies, along with examples can be found in articles by Clark and Khademi. (3) (4)

Maintaining the dentine in the peri-cervical region whilst achieving the goals of endodontics give this tooth the best possible chance of survival. Ultrasonics and copious irrigation allow the cleaning of the pulp chamber space and canal spaces without the need for excessive removal of tooth structure.

The restricted access still give good straight line access to the canal orifices. But see how much solid tooth structure remains? It does, however make the job of performing high quality endodontics more difficult. But what’s more important? Us having an easy time of it, or giving the patient the best possible long term outcome?

Limiting tooth destruction becomes a greater challenge when attempting to treat teeth with calcified pulp chambers or canals. When attempting to work through pulp chamber calcification or locate these difficult to find canals it can be easy to remove vitally important dentine. Assessing the degree of calcification prior to attempting treatment is the key to preventing this iatrogenic damage to teeth. Additionally, if upon access the location of all canals is difficult, it may be better to consider referring at that early stage, rather than to damage the tooth’s long term prognosis in an attempt to locate a difficult to find and prepare canal.

One important aspect of learning to limit the removal of healthy tooth structure for access is that it actually makes endodontic procedures much more difficult (especially in second and third molars) and increases the chances of missing canals, so you need to balance these potential issues with benefits of doing so.

1. Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: An epidemiological study. J Endod. 2004;30(12):846-50.

2. Vire D. Failure of endodontically treated teeth: classification and evaluation. J Endod. 1991;17:338-42.

3. Clark D, Khademi J. Modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am. 2010 Apr;54(2):249-73.

4. Clark D, Khademi JA. Case studies in modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am. 2010 Apr;54(2):275-89.