CRACKED TEETH: Classification

Cracked teeth can be one of the most complex, confusing and frustrating dental problems we face in every day practice. Its estimated in general practice that at least one patient per week presents with symptoms relating to a cracked or fractured tooth. Accurate diagnosis and correct management are obviously the crucial steps of successful treatment, but we need to start by defining the various crack types to ensure we are all talking about the same thing at the same time.

It is important for us to have a clear understanding of what is meant by each definition as this allows discussion of the characteristics, prognosis and reliable treatment planning for each crack type. There are many classification systems out there for cracked teeth. Thankfully, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) has developed a simple classification system for longitudinal tooth fractures based upon their location, direction, and extent. Not everyone out there agrees with this classification, but it’s the best we have and a good starting point when trying to manage.

Craze Lines

Craze lines occur only within enamel. They run parallel to enamel rods and terminate at the DEJ (Bodecker et al. 1951). Craze lines are present in most adult teeth. Various patterns of infraction lines can be seen depending on the direction and location of the impact to enamel, i.e. horizontal, vertical or diverging. Anterior teeth often exhibit vertical craze lines, involving the incisal edge or proximal corners. Posteriorly, craze lines usually cross the marginal ridges and extend along buccal and lingual surfaces.

Fractured Cusp

Fractured cusps occur most frequently in heavily restored teeth, where the marginal ridge is weakened and the affected cusp has insufficient support (Kahler 2008). A fractured cusp involves a complete or incomplete fracture initiated from the crown and extending subgingivally, usually directed both mesiodistally and buccolingually (Rivera & Walton 2008). The fracture usually crosses the marginal ridge, and also tracks down a buccal or lingual groove. It extends to the cervical third of the crown or root.

Fractured Cusp

Cracked Tooth

A cracked tooth is an incomplete longitudinal fracture originating in the crown and extending apically. Often cited as being only in a mesio-distal direction (Rivera & Walton 2008), the literature also reports an significant number of bucco-lingual fracture planes (Seo et al. 2012). It may extend through either or both of the marginal ridges, through the proximal surfaces and onto the root surface. Occlusally, the crack is more centred and apical than a fractured cusp and therefore more likely to cause pulpal and periapical pathosis (Rivera & Walton 2008). A cracked tooth may progress to a split tooth.

Cracked Tooth

Split Tooth

A split tooth is a complete fracture originating in the crown and extending subgingivally, directed most commonly mesiodistally through both marginal ridges and proximal surfaces (Seo et al. 2012). The split root area is often in the middle or apical third and tends towards the lingual. The more centred the crack is on the occlusion, the further apically the split extends. The segments are entirely separate and although it may occur suddenly it may be considered as a continuum from an incompletely cracked tooth (Rivera & Walton 2008).

Split Tooth

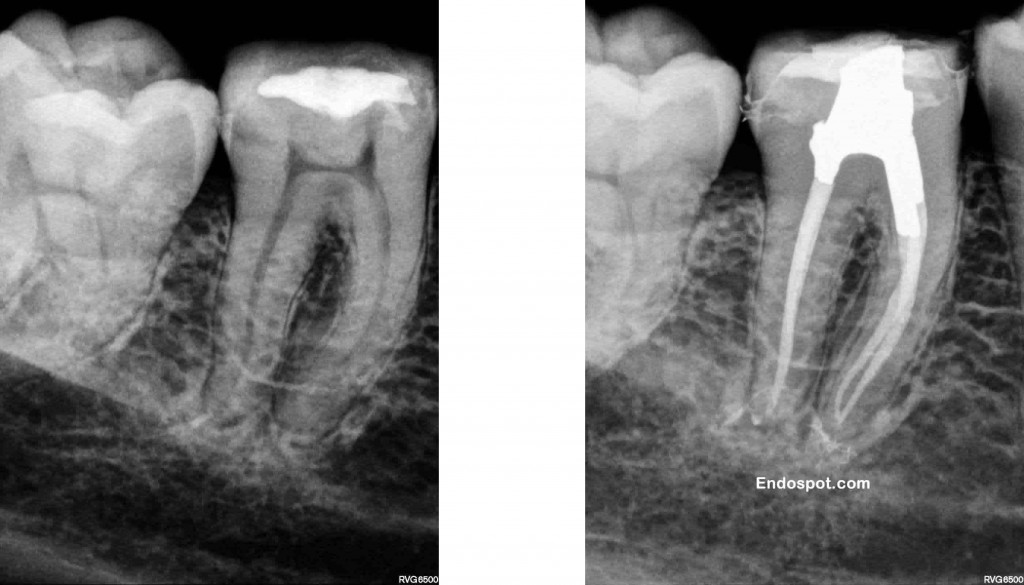

Vertical Root Fracture

Vertical root fractures are complete or incomplete fractures initiated from the root (at any level), usually directed buccolingually (Rivera & Walton 2008). Most occur in endodontically-treated teeth although the literature reports occurrences in non-root filled teeth (Yang et al 1995). A VRF may progress coronally and/or apically from the point of origin in any part of the root.

Vertical Root Fracture

Now we’re all on the same page, take a look at the next post in this series: Management of Cracked Teeth for an overview of recommended treatment strategies.

REFERENCES

Bodecker, CF, Gottlieb, B, Orban, B, Robinson, HB, Schour, I, Sognnaes, RF 1951. Enamel lamellae. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol, vol. 4, 787-98.

Kahler, W 2008. The cracked tooth conundrum: terminology, classification, diagnosis, and management. American Journal of Dentistry, vol. 21, 275-82.

Rivera, EM, Walton, RE 2008. Cracking the Cracked Tooth Code: Detection and Treatment of Various Longitudinal Tooth Fractures. Endodontics Colleagues for Excellence, Summer 2008.

Seo DG, Yi YA, Shin SJ, Park JW (2012) Analysis of factors associated with cracked teeth. Journal of Endodontics 38(3), 288-292.

Yang SF, Rivera EM, Walton RE (1995) Vertical root fracture in nonendodontically treated teeth. Journal of Endodontics 21(6), 337-339.

Along with some other enlightening speakers, I just had the pleasure of listening to a full day of lecture material by Dr John Ioannidis. Dr Ioannidis is a leader in the field of Epidemiology and Research Statistics. In 2005 he authored an article entitled, “Why Most Published Research Findings are False”.

Along with some other enlightening speakers, I just had the pleasure of listening to a full day of lecture material by Dr John Ioannidis. Dr Ioannidis is a leader in the field of Epidemiology and Research Statistics. In 2005 he authored an article entitled, “Why Most Published Research Findings are False”.